If you love Florence, or are just starting to delve into its history, you’ll soon discover that some pages of its past remain hidden, almost like details the city reveals only to those who are willing to listen. One of these is undoubtedly the period in whichFlorence was the capital of Italy: a short, intense and decisive chapter, which often surprises those who encounter it for the first time.

In this article, we retrace the stages of this journey together: when Florence became the capital, why it was chosen, how the city’s face changed, and what traces of those years you can still recognize as you stroll through 19th-century avenues, public buildings, and views that convey a history different from the Renaissance one we’re accustomed to.

A journey through nineteenth-century Florence, in short: a city that, within a few years, found itself at the center of Italian political life.

When Florence was the capital of Italy

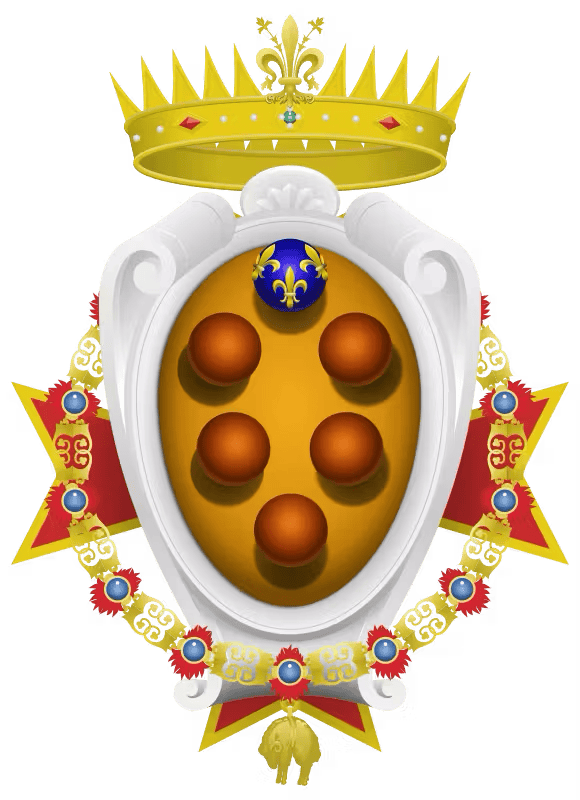

Florence officially became the capital onFebruary 3, 1865, in a still young Italy, still seeking balance. Unification had only recently been completed, and the country was still defining its identity. Turin, the Kingdom’s first capital, was no longer considered the ideal location, while Rome, which would later become its final seat, was still out of reach, under the control of the Papal States.

For this reason, Florence became a sort of intermediate solution: culturally important enough, geographically central enough, and above all “neutral” enough to withstand such a delicate transition. Parliament moved here, as did much of the administration and institutions, transforming city life in ways the Florentines themselves had never imagined.

The period lastedsix years, until1871, when Rome was finally annexed and became the permanent capital. But those six years were anything but marginal: the city began to change face, to expand, to modernize. New neighborhoods, new avenues, new functions: Florence suddenly discovered itself to be larger than it had imagined.

Why was Florence chosen as the capital?

When you think of nineteenth-century Italy, it’s easy to imagine a young nation still searching for its true form. After unification, the choice of capital was far from obvious: Turin had led the political process, Rome was the ultimate goal, but in the middle, a city capable of representing balance was needed.

Florence entered this picture for several reasons. It was considered a “central” city in the new Kingdom, both geographically and culturally.language Italian, as we imagine it today,largely originates here: a very strong symbol for a country that was trying to recognize itself as a nation.

However, diplomatic and very concrete reasons also counted. In 1864, Italy signed an agreement with France, the so-calledSeptember Convention, which included, among other provisions, the transfer of the capital from Turin. Florence was chosen because it was a prestigious city, less exposed to the conflicts of the time, and flexible enough to accommodate such a significant change.

Choosing it meant, ultimately, choosing a place that already embodied the idea of Italian culture. Not Rome, which had yet to be liberated, nor Turin, tied to a past too recent: Florence offered a sort of “neutral ground,” yet rich in meaning.

For the Florentines it was a sudden change: within a few months the city prepared to welcome ministers, officials, offices and a new rhythm of life that would remain imprinted for generations.

What changed in Florence during the years as capital

Becoming the capital was not just a matter of titles or administrative transfers: for Florence it meant changing rhythm, habits and even form. In those six years the city underwent a transformation that marked thebeginning of modern Florence.

One of the most obvious changes was the movement of people: thousands of officials, employees, soldiers, and families arrived from all over Italy. The streets filled with new dialects, new professions, new needs. Florence was more crowded, more dynamic, more “national” than it had ever been.

To accommodate all this, thecity had to adapt quickly. Entire neighborhoods changed face: public spaces were expanded, new avenues were created, and many historic buildings were converted to government functions. Palazzo Vecchio housed the Chamber of Deputies, while Palazzo Pitti became the royal residence: places we visit today for their artistic history, back then they were places where decisive political decisions were made.

But the most profound transformation was urbanistic.architect Giuseppe Poggi, charged with “modernizing” the city, designed projects that would forever impact the Florentine landscape. The medieval walls, which for centuries had surrounded the historic center, were demolished to make way for the nineteenth-century avenues still recognizable today. The idea was to give Florence a more open, luminous, European feel: a city capable of embracing its new political role without sacrificing its identity.

These works changed not only the city’s appearance, but also the Florentines’ perception of Florence. For some, it was progress, for others, a blow: a rapid and sometimes difficult-to-understand change.

Today, strolling along the tree-lined avenues or gazing at the orderly layout of certain areas, it’s easy to forget that it all began in that brief period when Florence was the heart of Italy.

Traces visible today: what remains of Florence as capital city

Although its role as capital was short-lived, Florence never truly returned to its former self. There are corners of the city that still bear the imprint of those years: you don’t need to be a history expert to notice them, you just need to know how to look while strolling.

The most obvious change is the19th-century structure surrounding the historic centerThe wide, regular, tree-lined avenues are the direct result of Giuseppe Poggi’s grand urban planning project. Where the medieval walls once ran, a more open, brighter Florence emerged in those years, closer to the European capitals of the time.

Many public buildings, scattered between Oltrarno and the city center, still retain the function or appearance they acquired during those six years. Palazzo Vecchio housed the Chamber of Deputies, and Palazzo Pitti became the royal residence.

Some areas were completely redesigned to accommodate offices, archives, and administrative staff. Not all of these spaces are open to visitors today, but knowing that they once played host to Italian political life adds a different dimension to their observation.

There are also less obvious, but equally significant, traces. Some neighborhoods developed specifically to accommodate the new incoming population: officials, families, and artisans who came from all over the peninsula. Florence, accustomed to a more measured pace, suddenly became a “national” city, more vibrant, more diverse.

If today you happen to pass through certain areas that seem a little different from the rest of the city, more orderly and more linear, it’s likely they carry with them the legacy of that period.

Revisiting these places with an awareness of their history allows us to see Florence through different eyes: not just as a Renaissance city, but as a living organism that, over time, has adapted, changed, and reinvented itself.

Curiosities and anecdotes about Florence as the capital

Describing Florence as the capital also means focusing on those details that rarely end up in history books, but which help us imagine the atmosphere of the time.

One of the most remembered episodes is thearrival of Vittorio Emanuele IIWhen the king arrived in the city in February 1865, Florence prepared as if for a great celebration: streets lit up, palaces decorated, crowds lined the route to the Pitti Palace, which would become the new royal residence. For many Florentines, it was an almost surreal moment: their city suddenly became the center of Italian political life.

No less significant was the way in whichthe capital transformed daily lifeForeign delegations, journalists, intellectuals, and bureaucrats of all ranks arrived in Florence. Inns filled up, trade increased, rents rose. Some Florentines saw this ferment as an opportunity; others, more attached to the city of the past, struggled to recognize certain changes.

There is also a detail that many visitors are unaware of: some urban planning interventions linked to the period as capital immediately aroused contrasting opinions.

The demolition of the medieval walls, for example, divided the city’s citizens. For some, it represented a necessary step toward a more modern city; for others, a painful sacrifice of urban memory. A century and a half later, those decisions continue to influence how we perceive Florence.

Finally, it’s worth remembering that in those years, Florence also became a vibrant cultural hub. Artists, writers, and politicians gathered in cafés and private rooms to discuss ideas, reforms, and visions of a new Italy. The city seemed to possess two souls: the ancient one, firmly rooted in the centuries, and the modern one, which sought to imagine itself as a protagonist of the future.

It is precisely these interweavings, the historical facts, the daily transformations, the urban planning choices, that make the period of Florence as capital so fascinating to rediscover today.